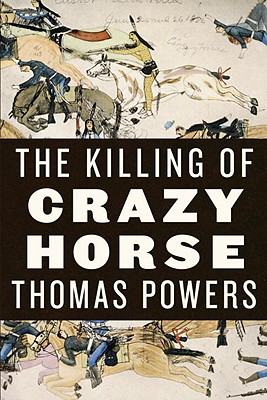

He was the greatest Indian warrior of the nineteenth century. His victory over General Custer at the battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 was the worst defeat inflicted on the frontier Army. And the death of Crazy Horse in federal custody has remained a controversy for more than a century.

He was the greatest Indian warrior of the nineteenth century. His victory over General Custer at the battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 was the worst defeat inflicted on the frontier Army. And the death of Crazy Horse in federal custody has remained a controversy for more than a century. The Killing of Crazy Horse pieces together the many sources of fear and misunderstanding that resulted in an official killing hard to distinguish from a crime. A rich cast of characters, whites and Indians alike, passes through this story, including Red Cloud, the chief who dominated Oglala history for fifty years but saw in Crazy Horse a dangerous rival; No Water and Woman Dress, both of whom hated Crazy Horse and schemed against him; the young interpreter Billy Garnett, son of a fifteen-year-old Oglala woman and a Confederate general killed at Gettysburg; General George Crook, who bitterly resented newspaper reports that he had been whipped by Crazy Horse in battle; Little Big Man, who betrayed Crazy Horse; Lieutenant William Philo Clark, the smart West Point graduate who thought he could “work” Indians to do the Army’s bidding; and Fast Thunder, who called Crazy Horse cousin, held him the moment he was stabbed, and then told his grandson thirty years later, “They tricked me! They tricked me!”

At the center of the story is Crazy Horse himself, the warrior of few words whom the Crow said they knew best among the Sioux, because he always came closest to them in battle. No photograph of him exists today.

The death of Crazy Horse was a traumatic event not only in Sioux but also in American history. With the Great Sioux War as background and context, drawing on many new materials as well as documents in libraries and archives, Thomas Powers recounts the final months and days of Crazy Horse’s life not to lay blame but to establish what happened.

TC history buff Mark L. says:

"I cannot recommend this book highly enough. Thomas Powers has done an excellent job of research, searching small details and manuscript collections. In addition,he can engagingly write about what he has found in his research--it is not every researcher who can research and write,as my years of reading history have shown me. "

Mark also recommends these titles on the subject:

Give Me Eighty Men: Women and the Myth of the Fetterman Fight

Give Me Eighty Men: Women and the Myth of the Fetterman Fight“With eighty men I could ride through the entire Sioux nation.” The story of the Fetterman Fight, near Fort Phil Kearney in present-day Wyoming in 1866, is based entirely on this infamous declaration attributed to Capt. William J. Fetterman. Historical accounts cite this statement in support of the premise that bravado and contempt for the fort’s commander, Col. Henry B. Carrington, compelled Fetterman to disobey direct orders from Carrington and lead his men into an ambush by an alliance of Plains Indians. In the aftermath of the incident, Carrington’s superiors positioned him as solely accountable for the “massacre” by suppressing exonerating evidence. In the face of this betrayal, Carrington’s first and second wives came to their husband’s defense by publishing books presenting his version of the deadly encounter. Although several of Fetterman’s soldiers and fellow officers disagreed with the women’s accounts, their chivalrous deference to women’s moral authority during this age of Victorian sensibilities enabled Carrington’s wives to present their story without challenge. In this fascinating book, Shannon D. Smith reexamines the works of the two Mrs. Carringtons in the context of contemporary evidence. Fetterman emerges as an outstanding officer who respected the Plains Indians’ superiority in numbers, weaponry, and battle skills. Give Me Eighty Men both challenges standard interpretations of this American myth and shows the powerful influence of female writers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Little Bighorn and Custer are names synonymous in the American imagination with unmatched bravery and spectacular defeat. Mythologized as Custer's Last Stand, the June 1876 battle has been equated with other famous last stands, from the Spartans' defeat at Thermopylae to Davy Crockett at the Alamo.

In his tightly structured narrative, Nathaniel Philbrick brilliantly sketches the two larger-than-life antagonists: Sitting Bull, whose charisma and political savvy earned him the position of leader of the Plains Indians, and George Armstrong Custer, one of the Union's greatest cavalry officers and a man with a reputation for fearless and often reckless courage. Philbrick reminds readers that the Battle of the Little Bighorn was also, even in victory, the last stand for the Sioux and Cheyenne Indian nations. Increasingly outraged by the government's Indian policies, the Plains tribes allied themselves and held their ground in southern Montana. Within a few years of Little Bighorn, however, all the major tribal leaders would be confined to Indian reservations.

In June of 1876, on a hill above a winding river called "the Little Bighorn," George Armstrong Custer and all 210 men under his direct command were annihilated by nearly 2,000 Sioux and Cheyenne. This devastating loss caused an uproar, and public figures pointed fingers in order to avoid responsibility. Custer, who was conveniently dead, took the brunt of the blame. The truth, however, was far more complex. A TERRIBLE GLORY is the first book to relate the entire story of this endlessly fascinating battle, and the first to call upon all the vital new forensic research of the past quarter century. It is also the first book to bring to light the details of the army cover-up--and unravel one of the greatest mysteries in US military history.