hikikomori, n. h kik mo ri; literally pulling inward; refers to those who withdraw from society.

Thomas Tessler, devastated by a tragedy, has cloistered himself in his bedroom and shut out the world for the past three years. His wife, Silke, lives in the next room, but Thomas no longer shares his life with her, leaving his hideout only in the wee hours of the night to buy food at the store around the corner from their Manhattan apartment. Isolated, withdrawn, damaged, Thomas is hikikomori.

Desperate to salvage their life together, Silke hires Megumi, a young Japanese woman attuned to the hikikomori phenomenon, to lure Thomas back into the world. In Japan Megumi is called a “rental sister,” though her job may involve much more than familial comforts. As Thomas grows to trust Megumi, a deepening and sensual relationship unfolds. But what are the risks of such intimacy? And what must these three broken people surrender in order to find hope?

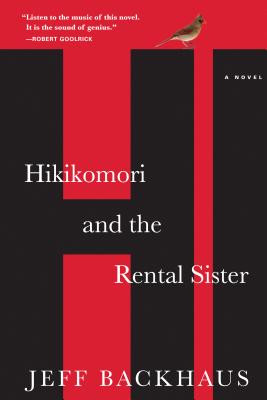

Revelatory and provocative, Hikikomori and the Rental Sister tears through the emotional walls of grief and delves into the power of human connection to break through to the waiting world outside.

Edward says:

"One of the profound effects a work of fiction can have on a reader is when the reader connects with a character (or characters) and is deeply moved by the circumstances at the very root of their conflict. Jeff Backhaus' book, Hikikomori and the Rental Sister, opens after Thomas Tessler and his wife, Silke, have experienced a debilitating loss. The grief is so strong that Thomas withdraws into his bedroom, away from his wife, as well as everything else, for three years. Without giving much more away of this stellar, yet disturbing book, consider this for a moment. What if the person who you care most about suddenly withdraws, while you, too, are trying to cope with a tragedy? Or, what if your pain is so great that it causes you to withdraw from everyone and everything, when what you may need most is a touch on the shoulder, a hug, or a light touch of a hand on your tear stained cheeks?

Silke loves Thomas so much. She wants to work through things, to help Thomas with these complex issues, but it has been three years and she has endured almost as much as she can. Silke has not been able to break him out of his self imposed shell, called hikikomori, in spite of making breakfasts, carrying on one sided conversations and even ordering anniversary meals. These scenes and dialogs are, at different times, pleading and sad, while at other times fueled by anger and frustration.

Thomas, however, does leave his room and the apartment in the middle of the night once he knows his wife is asleep. He walks the streets of New York in the snow to replenish his supply of canned goods and magazines. He returns before Silke wakes and withdraws yet again.

Silke seeks out the help of Megumi, whose own brother suffered from the same condition in Japan. As Silke is contemplates whether hiring Megumi as a "rental sister" will be successful or not, she asks, 'Does it work?' A part of Megumi's reply is, '...You want to see him and you want your life back, it's natural. But he's been in there for so long, your husband probably doesn't know how to come out of his room. So long that he's not sure if he knows how to live out here anymore.' Megumi sends a note to Thomas through Silke.

Thomas starts to refer to Megumi in his mind as the little pest but, she tells Thomas that she is not going anywhere. He does not open her note, but slides it back under the door. Megumi unseals it and pushes it back to Thomas. These very small interactions are the start of rebuilding Thomas' ability to interact with the world. Megumi talks to Thomas about taking a cool bath and about an onsen, a Japanese hot spring, located near Lake Placid. The description of these bath reengages Thomas' sexual longings and plants the seed for a spiritual experience. She slides an origami penguin under the door.

In her next visit, she shares with Thomas about her brother having the same condition and that he died before overcoming it. After confessing this, Thomas lets her into his room briefly until he realizes the state of his room, the odors, the filth. He yells at her to "Get out."

Thomas opens the door at her next visit as well though and they spend time learning how to say each other's names correctly. Backhaus shows how something as simple as saying each other's names helps build a bridge between cultural differences. As she describes the condition of hikikomori to him, he isn't alone. Backhaus follows this exchange with this wonderful description of a snow in New York.

'Thomas,' she says, careful to pronounce it correctly, 'it's snowing. Come look.' He joins her at the window. He is tall. She comes up only to his shoulders.

The snow falls gently. The wind forms the flakes into translucent sheets, tin curtains swaying back and forth.

'Isn't it beautiful?' she says. Thomas watches the snow bus says nothing. Megumi, too, says nothing for a time, the tow of them together at the window, watching. "Snow is gentle, but so powerful," she whispers. "Slows everyone down....makes everything quiet.""

This idea of quieting our minds, slowing down our pace and the busyness of our lives to give ourselves time to recover, to connect with people, reconnect with others is a powerful message, one I believe Jeff Backhaus masterfully portrays in Hikikomori and the Rental Sister.

A word of caution for some readers though. These scenes are juxtaposed with the often dark and difficult psychological scenes reminiscent of Pat Conroy's Prince of Tides. It is a haunting book. It will stay with you for days and weeks, if not months. As I have several books to review recently, I picked this one specifically because it was so heavy, so challenging, and has stayed with me. Jeff Backhaus has written a powerful work here. Don't overlook it."

No comments:

Post a Comment