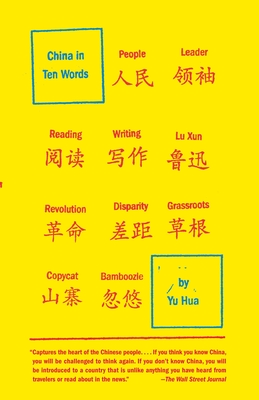

From one of China’s most acclaimed writers: a unique, intimate look at the Chinese experience over the last several decades.

Framed by ten phrases common in the Chinese vernacular, China in Ten Words uses personal stories and astute analysis to reveal as never before the world’s most populous yet oft-misunderstood nation. In "Disparity," for example, Yu Hua illustrates the expanding gaps that separate citizens of the country. In "Copycat," he depicts the escalating trend of piracy and imitation as a creative new form of revolutionary action. And in "Bamboozle," he describes the increasingly brazen practices of trickery, fraud, and chicanery that are, he suggests, becoming a way of life at every level of society. Witty, insightful, and courageous, this is a refreshingly candid vision of the "Chinese miracle" and all of its consequences.

Edward says:

"Yu Hua's collection of essays, China in Ten Words, traces the

path of China from the Cultural Revolution to the present day. The ten words are people, leader, reading,

writing, Lu Xun, revolution, disparity, grassroots, copycat and bamboozle.

The idea of people was synonymous with Chairman Mao and the

very name, the People's Republic of China.

One defining moment in his understanding of people came in the Tiananmen

Incident of 1989 when students flocked to the famous Square demanding democracy. The movement of the people seemed like it

would last forever and then ended as abruptly as it had began when the military

moved in and cleared the Square. He describes riding his bicycle toward Tiananmen

and being overwhelmed by the heat generated by so many bodies singing and

demanding change even though the evenings were cold when faced alone.

The essay on leader centered around Mao Zedong and his

larger than life presence in China.

Whether it was how he was represented in writing a big character poster

or swimming in the Yangtze River, he achieved an immortal type status. The only other leaders represented in

pictures were those of Stalin, Marx, Engels, and Lenin. It brought up memories of my own elementary

school days where the likenesses of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln grace

the walls. So influential was Mao that

his poems and quotations were often put to song. The man who had the good fortune of shaking

his hand would return to his village a celebrity. When the announcement of Mao's death was made

at schools, the students openly wailed and wept at the passing of their great

leader.

The chapter on reading traces a China which could read

openly and then was limited to only two works, The Selected Works of Mao Zedong

and the Little Red Book, Quotations from Chairman Mao. This

chapter details how Yu Hua had to get "bootleg" copies of classic,

forbidden works which had been handwritten and were passed from person to

person. They had often passed through so

many thousands of hands that the first and last 30 pages of the book would

often be missing. It wasn't until years

later that he finally learned how many books started and ended once books

became widely available again. One of

the most amazing stories in the entire book is related in this essay as Yu Hua

describes a scene reminiscent of people waiting in line for an IPod, but in the

case of China, it was to redeem book coupons when citizens were going to be

able to buy two books from a bookstore that was finally going to be able to

sell books for the first time since the Cultural Revolution.

The essay on writing describes his own path from a dentist

pulling teeth to becoming a writer. He

shares participating in his own family's big-character posters, drawing

similarities with blogs today. Later, as

he progressed from posters and gave his hand at writing plays, he visited a

well-known red pen (writer who professed the virtues of the Cultural

Revolution). Having grown up during the

Cultural Revolution, Yu Hua's knowledge of characters was limited, but his

Chinese critics often praised him because of his plain narrative language. A great quote that has often been recycled by

many writers in various countries with different backgrounds is repeated when

asked how he became a writer. "By writing." These two essays, "Reading" and

"Writing" make the collection worth your time.

The other essays follow other parts of Chinese culture and

its evolution to the modern day including China's hosting the Olympics, China's

inflated economic success, the role of grassroots success and revolution has

played at many different levels and on grand scales leading ultimately to

bamboozle. Because of China's world

influence though, these are having far reaching effects across many other

cultures and societies. The only

criticism I would have of the essays is that there is no epilogue bringing all

the ideas to a close.

This would be a wonderful book for those readers who are

already fans of Ha Jin and enjoy gaining a fresh perspective on China and its

continuing influence in the world arena.

This book reminds me of the glimpse or Iran that readers received when

reading Marjane Satrarpi's view of Iran in Persepolis or Loung Ung's Cambodia

in First They Killed My father."

No comments:

Post a Comment